Health Effects of Loneliness

What Loneliness Research Says About Illness and Cell Activity

Health News: Lonely People Have More Inflammation and a Less Responsive Immune System

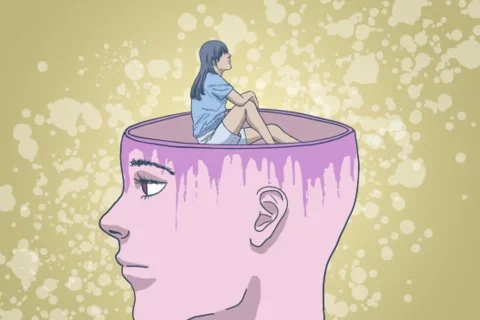

Researchers have long known that the health effects of loneliness, or perceived social isolation, can be substantial. People who fit this description often show a weaker immune response and greater inflammation than those who don't identify as lonely. This helps substantiate the widespread perception that mood can affect health, but why?

The cellular behavior at work here is fascinating to Steven W. Cole, PhD, professor of medicine, hematology/oncology in the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. His research focuses on the biological pathways by which social environments influence gene expression by immune cell genomes, as well as viral and cancer genomes.

White Blood Cells Hold the Key

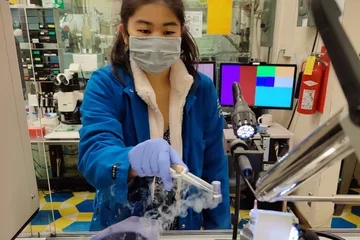

In this case, white blood cell gene expression—the process wherein genes control the production of specific proteins—seems to hold the answers.

Dr. Cole and colleagues from the University of California, Davis and the University of Chicago have published several papers discussing what they call "conserved transcriptional response to adversity," or CTRA, which describes an up-regulated inflammatory gene expression and down-regulated antiviral response. In other words, they have established a link between loneliness and CTRA that shows lonely people have more inflammation and a less responsive immune system.

The team's most recent findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, focused on gene expression in the leukocytes of both humans and rhesus macaques—a primate species known to be highly social. The leukocytes of lonely humans and macaques revealed the expected up-regulated and down-regulated gene expression patterns. But the paper also included intriguing new findings.

Loneliness, Gene Expression May Reciprocate

Specifically, loneliness predicted future CTRA gene expression measured over one year later. CTRA gene expression predicted loneliness measured more than a year later, too. This similarity between loneliness and leukocyte gene expression means that each one could contribute to the other. Researchers controlled for stress, depression and related factors and believe the findings are specific to loneliness.

In examining the cellular processes at work in macaque monkeys' CTRA gene expression, the team at the California National Primate Research Center found higher CTRA activity in the loneliest monkeys. They also displayed higher levels of norepinephrine, the so-called "fight-or-flight" neurotransmitter.

This builds on a previous finding that norepinephrine can stimulate the production of immature monocytes, which display high inflammatory gene expression and low antiviral gene expression.

Dr. Cole and his colleagues determined that both lonely humans and monkeys had a higher level of monocytes in their blood. Further investigation showed this to be due to increased production of immature monocytes. Monkeys experienced this effect following repeated mild social stresses, like being housed with unfamiliar cage mates.

Tangible Health Effects

Finally, a separate experiment showed that this cellular mechanism can directly affect physical well-being. When researchers introduced simian immunodeficiency virus (the equivalent of HIV in people) to lonely monkeys with impaired antiviral gene expression, these monkeys experienced faster growth of the virus.

Together, these findings support the idea that loneliness leads to fight-or-flight stress signaling. This results in increased immature monocyte production, up-regulation of inflammatory genes and down-regulation of antiviral responses. The conclusion is that it may lead to even deeper loneliness while increasing the associated health risks.

Dr. Cole and his colleagues will continue their research on the health effects of loneliness. They ultimately hope this work can lead to strategies for preventing these effects in older adults, contributing to improved health outcomes.

(Related Article: Finding a Cure for Loneliness)