The UCLA PhD Student Hoping to Disarm Bacteria

Nikki Cheung's vision for counteracting antibiotic resistance

Meet Nikki Cheung

Antibiotics help the immune system fight potentially deadly infections.

Antibiotics have saved countless lives since entering the clinical landscape in the early 1900s. During that same time, however, some bacteria learned how to resist them. These resistant bacteria may still infect hosts, despite the administration of antibiotics.

When bacteria resist antibiotics, drugs once clinically proven effective could fail against the same infections.

Collectively, antibiotic resistance poses a serious and growing threat to human health. In 2019 alone, investigators linked antibiotic resistance to nearly 5 million deaths globally.

"An antibiotic resistant crisis could be absolutely detrimental to our society," says Nikki Cheung, a PhD student in UCLA's Graduate Programs in Bioscience Biochemistry, Biophysics, and Structural Biology Home Area.

Nikki wants to prevent such a crisis by disarming bacteria—by making them less infective. She's examining their structural biology to learn how.

- Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) program: UCLA Graduate Programs in Bioscience - Biochemistry, Biophysics & Structural Biology Home Area

- Overarching research question: Can we make bacteria less infective?

- Recent honors: Nikki earned a 2024 Science Olympiad Alumni Research (SOAR) Grant for Medical Research Impacting Human Health for her promising approach to antibiotic resistance.

- Fun fact: Nikki's pet cockatiel, Stein, has a talent for singing. Nikki wants him to learn "September" by Earth, Wind, and Fire.

Solving the Structures of Proteins

Much like Velcro's® structure of tiny interlocking loops enables it to stick to things, bacteria's unique protein structures help it stick to host cells and ultimately infect them.

Before Nikki can hope to disrupt the structural underpinnings of bacterial infection, she must understand how, on a deep cellular level, all the structures function. It's a puzzle—one she's been looking forward to solving her entire life.

"I've always wanted to solve the structures of proteins, " Nikki says. "I always wanted to look at proteins and see how they function and how they interact within the cell."

Solving this puzzle comes with life-changing rewards.

Nikki's research findings could one day inform the development of novel drugs that don't merely treat infection but instead block bacteria, including the antibiotic resistant kind, from infecting cells in the first place.

Finding the Right Research Community

Nikki took a straightforward approach to finding a PhD program: Knowing she wanted to study structural biology specifically, she simply looked for the best-possible place to do it.

"UCLA's structural biology program is unmatched," she says. "I couldn't see myself going anywhere else for the work I wanted to do."

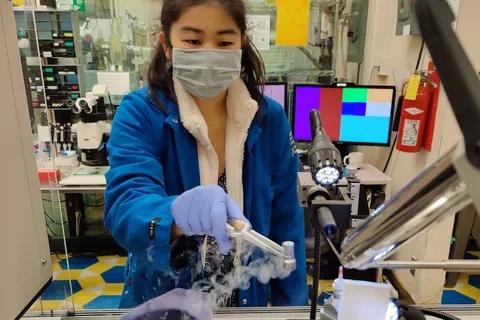

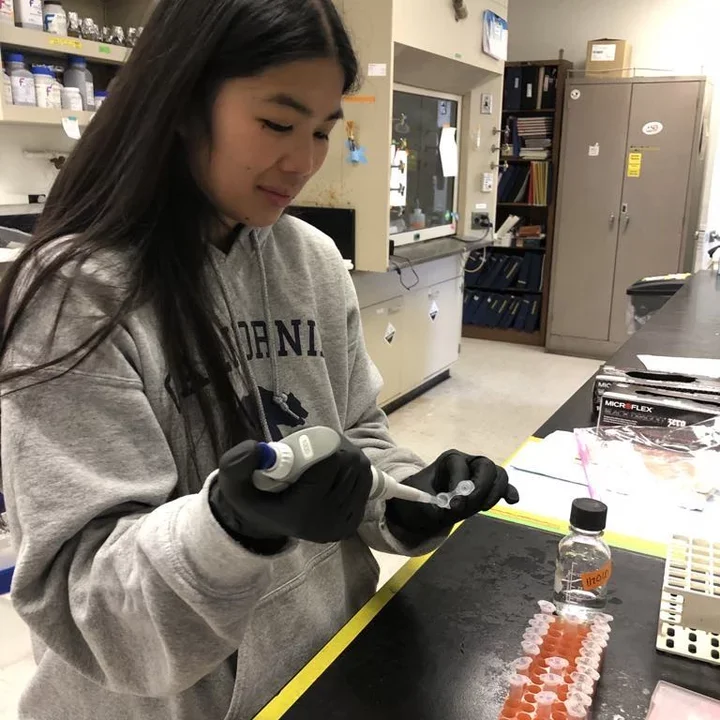

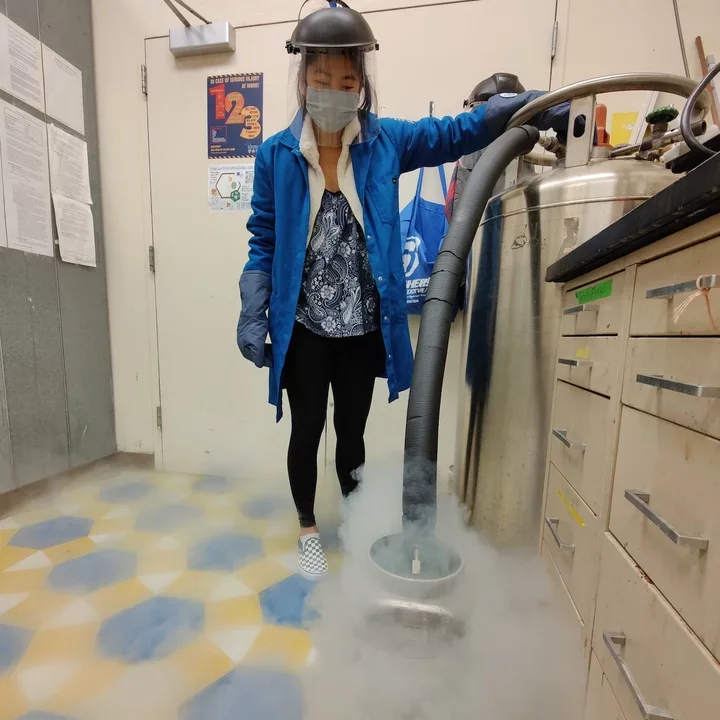

At UCLA, Nikki's doing the work she always wanted with all the resources, equipment, and community support she could ever want. She experiments with the most advanced techniques in her field, including cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and x-ray crystallography. She leans on robust support from mentors and peers.

"My mentor, Dr. Robert Clubb, always helps me strive to do everything I want to do," she says. "And his entire lab is so supportive. We're truly all really great friends and enjoy working with each other every day."

When Nikki's not solving structural biology puzzles in the Clubb Lab, she chooses from a constellation of both on- and off-campus recreational opportunities. On any given free day, she might choose between going to the beach or picking up an Irish dance class.

"At UCLA, there's something for everyone. There are ways to pursue practically any interest—athletic, academic, and recreational."

Advice for Aspiring PhD Students

Nikki is deeply committed to a career in structural biology now. As a high school student, she didn't even know there was such a field—or higher education programs centered around it.

"I'm the first one in my family who went into a science career."

Nikki learned about careers in science by participating in an outreach program. It gave her the chance to conduct research in university labs.

"That was when I learned that PhD programs exist."

Inspired, Nikki volunteered teaching extracurricular science to young children with limited access to quality resources and education.

Thanks to these opportunities, Nikki had a strong understanding of her field before she applied to advanced programs. She urges aspiring PhD students to pursue similar tracks, and when possible, to avoid overthinking the application process.

While it's easy to feel stressed, daunted, and even judged, the process is ultimately about helping each candidate find an environment where they can thrive.

"When you get there—when you get to do the research that you want to do, it's beyond rewarding," she says. "You'll see your work come to fruition. Then you'll know all the stress you may have gone through was worth it."