Medication for High Triglycerides

New Drug Takes an Innovative Approach to Lowering Triglycerides

Health News: New Medication Could Be Big Breakthrough in Heart Disease Treatment

An experimental drug might give cardiologists a new resource in the fight against heart disease. The medication has years worth of clinical trials to undergo before it may be released. However, early results reported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) suggest it has potential for lowering triglycerides by up to 70.9 percent.

Triglycerides (blood fat) are the most common type of fat in a person's body, according to the American Heart Association. People with high cholesterol, heart problems or diabetes often have elevated levels of this substance. The same is true for overweight individuals and those who suffer from genetic conditions such as inherited chylomicronemia syndrome, which limits the body's ability to break down these types of fat.

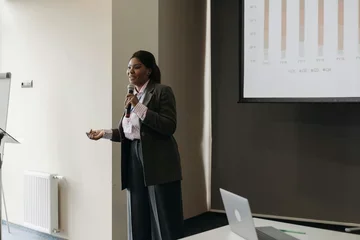

Blood tests reveal whether or not a person's triglycerides fall into a healthy range, which typically implies less than 150 mg/dL. "If your triglyceride level is over 500, the biggest threat to life is pancreatitis," says Dr. Karol E. Watson, a practicing cardiologist, professor in the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and co-director of the UCLA Program in Preventive Cardiology. "But even more minor elevations, in the 200 to 300 range, can increase your long-term risk of developing heart disease."

Considering heart disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S., even small strides to minimize one's risk factors could go a long way. "Triglycerides have a less clear role in heart disease," says Dr. Watson. "They certainly promote it, just not as much as LDL ('bad' cholesterol). But targeting all these particles can help reduce our risk."

A High-Tech Approach to Lowering Triglycerides

Current treatment for lowering triglycerides starts with lifestyle changes: losing weight, avoiding saturated and trans fats, reducing sugar and alcohol intake, smoking cessation and exercising. Doctors also can prescribe niacin or a class of drugs called fibrates, but these medications aren't effective on all patients.

The new drug targets a protein called apolipoprotein C-III, which slows the breakdown of triglycerides. By neutralizing this protein, the new medication effectively speeds up this breakdown so it doesn't accumulate in unhealthy amounts.

"Current medications try to prevent you from releasing triglycerides or help you increase the removal of triglycerides," Dr. Watson says. "This drug uses a brand new strategy. It allows your body to carry all the genetic machinery necessary to make high triglycerides, but then it uses antisense technology to inactivate your genetic machinery before it gets a chance to produce the critical components of triglycerides. You never get a chance to put them together so they never get released."

The Results So Far

The U.S. requires three drug trials before new medications are eligible for FDA approval, and the new drug has begun its third trial, but the final results won't be available for several years.

For the second trial, explains the NIH, researchers treated 57 patients with triglyceride levels between 350 and 2,000 mg/dL who were not already receiving drug therapy, and 28 patients who were taking fibrate medications. Subjects received weekly doses of either the drug or a placebo. After 13 weeks, those taking the drug experienced a 31-to-71-percent reduction in triglycerides.

Dr. Watson sees these results as promising, but she does not want to celebrate too early. "We've been hopeful many times before, but only a handful of medical interventions that look promising ever actually make it to clinical use," she says. "However, there really is [an] exciting pipeline of medicines designed to treat or reduce cardiovascular risk. We don't know which will work—maybe none, maybe all—but the future certainly looks like it could be pretty great."