What Does a Urologist Do?

A UCLA Doctor Explains

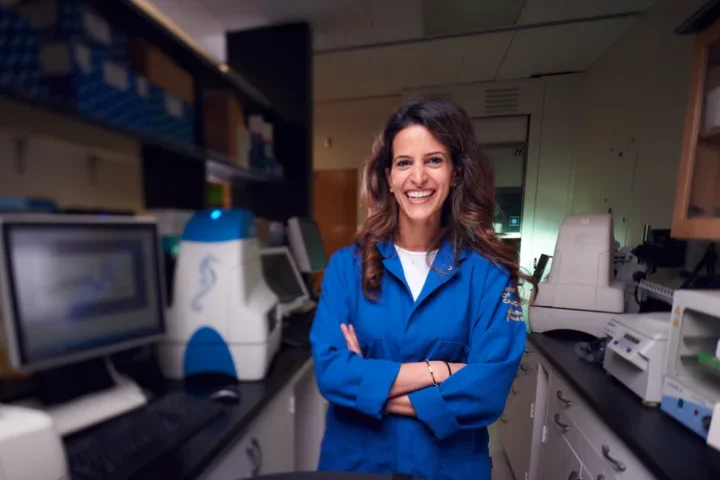

A Day in the Life of Dr. Stephanie Chu, UCLA Urologist

Dr. Stephanie Chu, MD, didn't plan on becoming a urologist. An environmental science major, she wanted to be a backpacking instructor.

Halfway through undergrad, Dr. Chu changed her mind. "I wasn't helping any particular person with environmental science, so I switched to environmental health," she says. "Then I took a first-aid class and loved it." So, Dr. Chu hung up her backpack and applied to the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

What attracted her to urology? And exactly what does a urologist do?

(What Is a Urologist? Click the link to learn more...)

A Well-Rounded Specialty

Ten years ago, Dr. Chu's chosen specialty would have seemed as unlikely as her career path. But today, according to the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), 25 percent of urology residents are women.

Despite common misconceptions, urologists treat more than the male reproductive system. "Urology also covers the entire urinary tract," says Dr. Chu. "Some urologists even specialize in vaginal reconstruction."

Dr. Chu says urology was a natural fit for her. "I wanted to do surgery," she explains. "But in many surgical fields, the treatment path is clear before surgeons get involved. I like participating in diagnoses and medical management. I like counseling patients, talking them through the big picture and helping them make informed decisions."

In urology, Dr. Chu found the surgical-medical balance she wanted, and a job that "never gets boring."

What Does a Urologist Do?

A typical day for Dr. Chu varies. A second-year resident, she works with attending urologists at various UCLA hospitals and clinics.

When she's at a hospital, Dr. Chu arrives around 6 am. "I see patients on the urology service, review their information and discuss treatment plans with the attending [physician]. I propose what I'd like to do, and the attending agrees or disagrees, then explains why."

Next, Dr. Chu heads to the operating room, where her team performs three to seven surgeries. "The purpose of residency is to coach newly graduated doctors to become surgeons," she says. "Depending on how far along we are, we either observe, learn certain steps or participate while being proctored by the attending."

The surgeries urologists perform most often depend on the practice. DGSOM hosts a busy kidney transplant program, so urologists do hundreds of transplant surgeries each year. "Our urologic oncologists perform prostate, bladder and kidney cancer surgeries," says Dr. Chu. "We also have a kidney stone specialist, and a world-renowned urologist with a female pelvic reconstruction practice."

The Coolest Toys

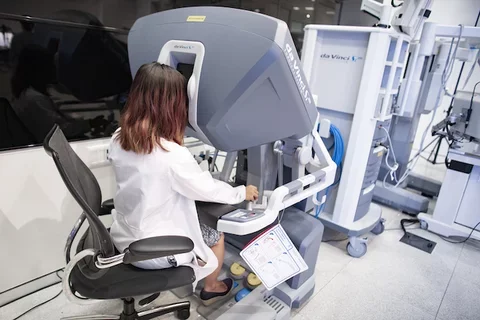

Over the past decade, technology has shifted urology toward more minimally invasive procedures. Dr. Chu explains, "We can go into the urethra, through the bladder and look into the kidneys without making a single incision. Surgeries to remove prostates or kidneys, which once required open surgeries, can be done laparoscopically — with tiny, image-guided instruments — or robotically."

Using the da Vinci™ surgical system, surgeons sit at a console with their fingers in sensors, remotely controlling a robotic surgeon with multiple arms. "This gives surgeons more joints inside the body, allowing them to move in ways that would be impossible laparoscopically."

The result for patients: Less blood loss and scarring, and a faster recovery.

"That's another reason I love urology," says Dr. Chu. "We have the coolest toys."

Advice for Future Doctors

Urology might not seem like the most glamorous surgical specialty, but perceptions shouldn't factor into doctors' career decisions.

"When you choose a field, you'll be doing it for decades, so initial reactions are worth getting past," she advises. "I often hear, 'Why urology? That's gross.' If I were a neurosurgeon, people would say, 'Cool, you operate on brains.' But that coolness factor wears off quickly, so medical students should consider what they enjoy doing. They'll be happier, making them better doctors."