Brain Tumors

Glioblastoma

One Of The Worst Types of Cancer

Tremendous progress has been seen in cancer treatment in recent years as doctors identify which specific drugs will work on certain types of cancers and refine the accuracy of surgery and radiation. However, the brain is a special organ, and it's not surprising that tumors arising in the brain pose special challenges. About 78,000 Americans are diagnosed with a primary brain tumor each year; about one-third of those tumors are malignant. Too often, these cancers strike people in the prime of life. Malignant brain tumors are the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in adolescents and young adults ages 15 to 39. One of the most common types of malignant brain tumors is called glioblastoma. More than 12,000 glioblastomas are diagnosed each year in the United States and the prognosis is typically poor—among the worst of all types of cancer.

“ ”

Glioblastoma Research

Faced with such dismal odds, UCLA researchers have sought to better understand the biological underpinnings that give rise to brain cancers and create smarter therapies to improve survival. Research is exploring the different genetic subtypes of glioblastomas to characterize their differences and how treatments might vary according to the tumor subtype.

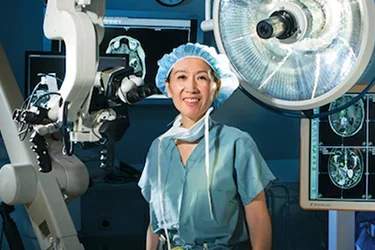

After almost two decades of research, one of the most innovative treatments for glioblastoma, a patient-specific brain tumor vaccine, is in a phase-3 clinical trial. The DCVax-L vaccine was pioneered by Dr. Linda Liau, a professor of neuro-oncology and director of the UCLA Brain Tumor Program. The vaccine is based on the idea that the body's immune system fails to recognize cancer cells as foreign invaders and attack the cells.

Early studies showed the safety of the vaccine is acceptable, and subsequent research revealed that some patients survived far longer than expected. "The issue is that it doesn't work for everyone," Dr. Liau says. "We're still trying to find out what are the biomarkers of response in these patients? Which patients will respond well and which won't? And is there a way to detect that ahead of time so we can pick out the 25 percent of patients we know will be helped?"

Glioblastoma Treatment

UCLA researchers are also exploring whether the personalized vaccine will be more effective if patients also receive other therapies in combination. For example, several new immune system therapies trigger the body's immune system, the T cells, to fight cancer.

"Right now, treatment for glioblastoma is still surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. But I think treatment for glioblastoma is going to be much more personalized in the future. We will need to have good biomarkers, genetic signatures for these tumors, (and a deeper understanding of the biology of different tumor cells) and then we'll be able to sort patients into the correct treatment depending on the type of brain tumor they have."