Intervention Research

Autism Treatment And Intervention Research

A History Of Innovative Therapeutic Approaches

UCLA has a long history of treating children with autism and teaching various behavioral and cognitive therapies to parents, caregivers and teachers. This research has revealed that, despite mysteries surrounding the cause of the condition, children can improve with intensive, personalized therapy. Progress in the field, however, has relied on the careful collection of data and adherence to the highest research methodologies. UCLA researchers have fundamentally changed autism treatment by testing and studying innovative therapeutic approaches in clinical trials and publishing their findings in peer-review scientific journals. Children benefit, and so does science.

"Treatment research has really exploded, such as behavioral and cognitive treatments," Dr. Geschwind says. "Dr. Kasari and her group are beginning to provide us with an understanding as to what are the active ingredients of therapies and how to maximize that for individual patients."

Intervention research is based on several core principles, says Dr. Kasari:

- Embracing innovation as the driver of progress

- Knowing that different children require different therapies

- Understanding the biological mechanisms as well the as behavioral features of the disorder

- Melding of developmental and behavioral perspectives

Intervention research at UCLA tries to unite two theoretical treatment models on ASD that traditionally have been in conflict: a developmental approach, which focuses on helping children reach developmental milestones, and a behavioral perspective, which aims to change behaviors.

“Many of the things about children with autism are completely normal, but there are these gaps or deficits. We try to target those deficits by understanding neuronal development and improve outcomes by using some of the behavioral and developmental strategies.”

UCLA researchers have used both approaches with the central goal of identifying and addressing gaps in a child's development. A core deficit among many children with ASD is impairment in social communication. Even early in life, children with ASD may be socially disengaged. Babies don't look at their caregivers' faces as much or point at things or show things to others. Later, these same children may have delays in language acquisition. About 50 percent of children diagnosed with ASD at age 2 are still nonverbal or have minimal language by age 9. Yet until recently, little research was devoted to treatments for increasing language skills.

JASPER: Connected Interventional Strategy

Dr. Kasari leads several studies on interventions designed to minimize social and language deficits. She has developed a behavioral intervention called Joint Attention Symbolic Play Engagement and Regulation (JASPER) to help autistic children engage with others. The techniques involve a parent, caregiver or therapist playing with a child in a way that teaches the child how to interact with others and use language. Instead of leading a child through a series of drills, JASPER connects various therapeutic strategies in a setting that features playing with toys.

"JASPER is really focusing on engaging the child," Dr. Kasari explains. "It combines many strategies, and it works because it's all connected together. We really try to help kids make sense of their own environment."

Through multiple, controlled and randomized clinical trials, Dr. Kasari has shown that JASPER can improve social communication skills; it is particularly useful in children who are minimally verbal and have not responded as well to other therapies.

JASPER is being modified and evaluated in several types of studies, including research on high-risk babies. Called Baby Jasper, the program is a type of Mommy and Me play group that incorporates elements of JASPER into the class. Researchers want to know if this type of early intervention affects the developmental trajectory of high-risk children.

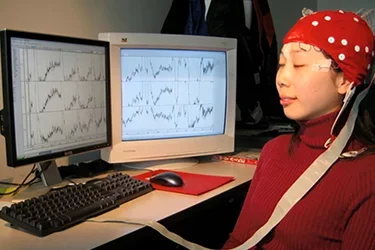

Researchers vigorously measure the results of the JASPER intervention and are even using brain imaging to look at what parts of the brain may be changing as JASPER is applied and children begin to engage socially and acquire language. This avenue of research represents an emerging paradigm for studies on targeted treatments by linking symptoms with the growing understanding of the core pathophysiology of the disorder.

Imaging and biomarker studies might also lead to better use of combination therapies. The autism center researchers are studying the drug aripiprazole, which stabilizes a chemical called dopamine that acts on a part of the brain involved in social motivation. The medication is prescribed to nonverbal children with ASD, ages 6–11, to see if it acts synergistically with JASPER therapy to improve language skills.

Interventional Therapy In Underserved Communities

A key component to the success of therapies like JASPER is whether they can be replicated in the real world. JASPER and other therapies are included in community-partnered research to test how well teachers working with autistic children in under-served communities can use the methodology. This type of research is particularly important to help level the playing field for children from economically disadvantaged communities. In the Los Angeles Unified School District, about 14,000 children have been identified as having ASD. About 75 percent of them are Latino, and 80 percent quality for free meals, a marker of low economic status. But a disproportional number of children receiving autism treatment and services are white, Dr. Kasari says.

"This data is showing that the disparities, even in public school systems, are real. So we're trying to change that," she says.

Researchers should be challenged to understand how to prescribe therapies logically to children based on evidence. Most children need multiple types of interventions, and there are questions about how to structure the order of those treatments. UCLA researchers are conducting "sequential multiple assignment randomized trials" — also known as SMART — which are designed to learn the optimal sequence of treatments for a child. The trials are aimed at understanding why a particular sequence may be superior and which children might benefit the most.

Innovation is a central principle for intervention research and it is critical to combat complacency and stagnation in the field, Dr. Kasari says.