The Different Types of Epilepsy

Research Spotlight

What You Need to Know About Epilepsy and Seizures

In This Article:

- Epilepsy Definition

- Epilepsy Types

- Seizure Types

- Epilepsy Symptoms

- Epilepsy Causes

- Epilepsy Diagnosis

- Epilepsy Treatment

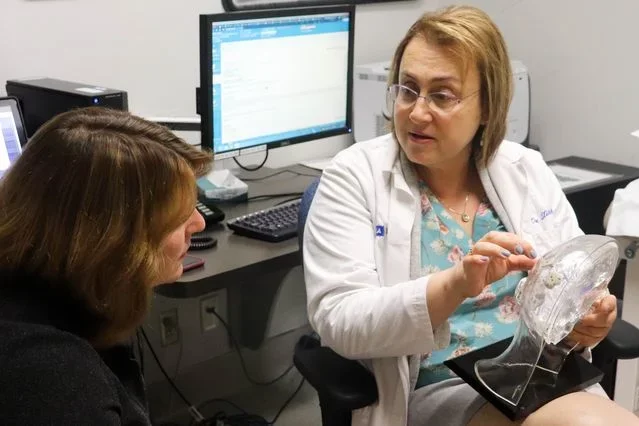

Meet Dr. Dawn Eliashiv

“I always want to offer hope. I can't always promise results. But I’m very stubborn and persistent, so what I can promise is that I will keep trying and not give up.”

Dr. Eliashiv—a UCLA Medical School Neurology Professor and Co-Director of the UCLA Seizure Disorder Center—has always been interested in the human brain: “What makes us unique is our ability to think, our ability to observe the world, and to care and interact with other people.”

An epileptologist who attended the Sackler School of Medicine and completed a fellowship in neurology at UCLA in the early 90s, her current interests focus on responsive neurostimulation in patients with medication-resistant epilepsy as well as using computerized morphometry to identify patterns in the hippocampus when a healthy brain develops epilepsy. Via the process of identifying biomarkers, she hopes to contribute to the creation of innovative interventions to prevent epilepsy, using MEG and other methods.

Why was Dr. Eliashiv drawn to epilepsy? “I like having an impact on people and improving their quality of life. And epilepsy affects everybody,” she explains. “Children, adolescents, and adults. Men and women.”

But most importantly, it’s an ever-evolving specialty where new discoveries are the norm rather than the exception: “There are always new treatments, new medications, new procedures, new diagnostic tools. So I’m always exploring new ways to help my patients, and I find that very gratifying.”

Read More: Multiple Treatment Options Available to Patients with Epilepsy

Epilepsy Definition: What Is Epilepsy?

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological condition that results in recurrent seizures. It is a disorder of the brain's electrical activity.

- Epilepsy vs Seizure: What’s the Difference?

The primary distinction between epilepsy and seizures is the recurrence. Epilepsy is defined by recurrent seizures, whereas a single isolated seizure does not necessarily indicate epilepsy.

Additionally, epilepsy is a specific neurological disorder with an underlying cause that leads to repeated seizures. In contrast, seizures and seizure disorders can result from a wide range of causes, both neurological and non-neurological.

“There are a lot of things that look like electrical epileptic seizures but they’re not,” cautions Dr. Eliashiv. “Some patients have psychogenic nonepileptic seizures or dissociative seizures. It's important to diagnose those accurately because those are usually treated with cognitive behavioral therapy rather than medications.”

- How Common Is Epilepsy? Is Epilepsy a Disability?

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 50 million people worldwide have epilepsy—making it one of the most common neurological diseases globally—and about 5 million individuals are diagnosed with epilepsy on an annual basis.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that about 3.4 million people, or approximately 1.2% of the population, have epilepsy.

While the specific impact of epilepsy on an individual's ability to perform essential job functions and the need for accommodations can vary, epilepsy is recognized as a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). This means that individuals with epilepsy are entitled to certain legal protections and accommodations in employment and public spaces.

Different Types of Epilepsy

Epilepsy can be divided into four different types according to the kind of seizures the patient is experiencing:

- Generalized Epilepsy: Seizures in generalized epilepsy involve widespread areas of the brain from the onset of the seizure. Subtypes include absence seizures, myoclonic seizures, tonic-clonic seizures, and atonic seizures.

- Focal Epilepsy: Seizures in focal epilepsy originate in one specific area of the brain. They can be further classified based on where they originate, such as temporal lobe epilepsy or frontal lobe epilepsy.

- Generalized and Focal Epilepsy: Patients with generalized and focal epilepsy experience both generalized and focal seizures.

- Unknown Onset: Occasionally physicians are certain that a patient has epilepsy, but they are unsure if the seizures are localized or widespread.

There are also several different kinds of epilepsy syndromes, such as Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, West syndrome, Rasmussen's syndrome, and Doose syndrome.

Different Types of Seizures

“The International League Against Epilepsy divides seizures into two different types: focal seizures and generalized seizures.”

Unlike the portrayals we often see in media, some seizures can actually go unnoticed because they’re so inconspicuous: “Not all seizures are generalized tonic-clonic seizures, where you see flailing movements, tongue biting, and loss of urine. A lot of patients have focal seizures, which are often more subtle. The patient may experience loss of contact or awareness, wide open eyes, lip smacking, tightening of one arm, or some repetitive movements. And those may last only 30 seconds to a minute.”

There are two types of Focal Onset Seizures:

- Focal Aware: Also called simple partial seizures, these seizures do not impair consciousness and may involve unusual sensations or movements localized to a specific part of the body.

- Focal With Impaired Awareness: Also called complex partial seizures, these seizures often affect consciousness and may involve repetitive, purposeless movements or actions.

There are several different types of Generalized Onset Seizures:

- Absence Seizures: These are characterized by a brief loss of awareness, often with staring and subtle movements. These used to be called petit mal seizures and last approximately 15 seconds.

- Myoclonic Seizures: These involve sudden, isolated muscle jerks or twitches and last for just a couple of seconds, though it’s not unusual for a patient to experience several myoclonic seizures over a short period of time.

- Tonic Seizures: Muscles become stiff, and the patient may fall.

- Clonic Seizures: These are characterized by repetitive, rhythmic jerking movements.

- Tonic-Clonic Seizures: These are the most well-known seizures, featuring loss of consciousness, stiffening of the body (tonic phase), and subsequent jerking movements (clonic phase). They were previously referred to as grand mal seizures.

- Atonic Seizures (Drop Attacks): These seizures cause sudden loss of muscle tone, leading to falls or head drops.

What causes seizures? According to Dr. Eliashiv, seizures happen when there is abnormal electrical activity in the brain because the patient’s neurons are firing all at once, thereby disrupting the brain’s normal network. It’s often compared to an “electrical brainstorm.”

Symptoms of Epilepsy

- How Long Do Seizures Last?

“It varies…” says Dr. Eliashiv. “Some patients wake up right away and five minutes later they're good to go. Some patients have clusters—one seizure after the other—and then their whole day is wiped out.”

In general, seizures typically last for a relatively short period, often a few seconds to a couple of minutes. However, some seizures can be more prolonged, especially if they evolve into status epilepticus, which is a medical emergency.

- What Does a Seizure Feel Like?

- Aura: Some people with epilepsy may experience an "aura" before a seizure. An aura is a warning sign, and it can manifest as a strange sensation, such as a smell, taste, visual disturbance, or déjà vu. “Some patients may experience fear or anxiety or a feeling of impending doom before a seizure, especially if they have focal seizures that originate in the temporal lobe.” This feeling can serve as a signal that a seizure is imminent.

- Loss of Awareness: During certain types of seizures, particularly complex partial seizures, individuals may have an altered sense of awareness or consciousness. They may not remember the seizure or what occurred during it.

- Physical Sensations: Seizures may involve physical sensations like muscle contractions, tingling, or numbness. Some people experience a feeling of being "frozen" or unable to move.

“In many cases, the seizure may last only one to two minutes but then the patient is confused for half an hour,” explains Dr. Eliashiv. “They wake up disoriented, possibly in the ER or an ambulance. And because we often administer drugs like lorazepam, they feel sedated. If the patient had a generalized seizure and bit their tongue, there’s also going to be pain or discomfort.”

- What Triggers Seizures?

Again, it varies according to each patient, but there are some common triggers for epileptic seizures:

- Lack of Sleep: Sleep deprivation can lower the seizure threshold, making seizures more likely to occur.

- Stress: Emotional or physical stress can trigger seizures in some people.

- Alcohol and Substance Abuse: The use of alcohol and certain drugs can provoke seizures.

- Missed Medications: Non-adherence to prescribed antiepileptic medications can increase the risk of seizures.

- Flashing Lights: Some individuals with photosensitive epilepsy may experience seizures triggered by flickering or flashing lights, such as from video games or strobe lights.

- Hormonal Changes: Some women with epilepsy may experience seizures related to their menstrual cycle or hormonal changes.

- Illness or Fever: Infections or high fevers can lower the seizure threshold, particularly in children.

- Medication Interactions: Certain medications can interact with antiepileptic drugs and reduce their effectiveness.

- Other Factors: Other factors, such as specific foods or environmental conditions, can act as triggers for certain individuals.

“I often compare seizures to earthquakes. Earthquakes are unpredictable, you don’t know when they’re going to strike, or how long they’re going to last. But there’s a loss of control.”

What Causes Epilepsy?

- Is Epilepsy Genetic? Is Epilepsy Hereditary?

According to Dr. Eliashiv, there are many causes of epilepsy and while human genetics may play a role, that’s not always the case: “Some patients have a family history, but for a lot of patients it's not genetic.”

What are the most common causes of epilepsy?

- Structural Brain Abnormalities: Epilepsy can result from structural issues in the brain, such as brain tumors, brain injuries, brain infections, or congenital malformations.

- Trauma: Head injuries or traumatic brain injuries can increase the risk of developing epilepsy.

- Metabolic Disorders: Some metabolic disorders can lead to epilepsy, particularly in infants and children.

- Stroke: Stroke can cause damage to the brain, leading to seizures and potentially epilepsy.

- Infections: Certain infections, like meningitis or encephalitis, can trigger epilepsy.

- Parasites: In many developing countries, there are parasites—such as neurocysticercosis (NCC)—that may cause epilepsy.

- Toxic Exposure: Exposure to certain toxins or substances can result in seizures and, in some cases, epilepsy.

- Genetic Factors: In some cases, there may be a genetic predisposition to epilepsy, and specific genes have been linked to the condition.

- Idiopathic Epilepsy: In many cases, the exact cause remains unknown. This is referred to as idiopathic epilepsy.

How Is Epilepsy Diagnosed?

Diagnosing epilepsy typically requires a comprehensive evaluation that may include several tests to confirm the presence of the disorder and determine its specific characteristics.

Neuroimaging: Imaging tests like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans are used to examine the structure of the brain. These scans can help identify structural abnormalities, brain lesions, tumors, or other conditions that might be causing seizures.

“We're not necessarily just looking for tumors,” advises Dr. Eliashiv. “For instance, sometimes we can see small scars or other evidence of conditions like cortical dysplasia (a defect where the top layer of the brain does not form properly during fetal development).”

“We also do a PET scan, which checks the metabolism of the brain. The brain is a heavy user of sugar (glucose). So we look at the areas of the brain that don't use sugar as much to pinpoint where the seizures might be originating.”

Electroencephalogram (EEG): EEG is a key diagnostic tool for epilepsy. It records the electrical activity of the brain. Abnormal electrical patterns or spikes in the EEG can be indicative of epilepsy. In some cases, a prolonged or ambulatory EEG may be necessary to capture seizure activity that does not appear during a brief routine EEG.

Video Monitoring: Video EEG monitoring combines video recording with continuous EEG recording. This allows doctors to observe the patient's behavior during a seizure and correlate it with the electrical activity in the brain. “Sometimes we admit patients to the epilepsy monitoring unit, where we use both video and EEG to try to actually capture these seizures or events.” This is especially helpful in characterizing seizure types and identifying their origin in the brain.

Neuropsychological Testing: In some cases, neuropsychological tests may be conducted to assess cognitive function and memory, which can be affected by epilepsy. “The neuropsychological testing helps us see if there are deficits in particular areas of the brain, like the frontal or temporal areas of the brain.”

It’s also important during the diagnostic process to rule out other potential causes for recurring seizures—such as alcohol withdrawal, certain drugs, metabolic abnormalities, and electrolyte disturbances—because the treatments will likely be different. As Dr. Eliashiv stresses: “You don't want somebody to be misdiagnosed and have the burden of being on the wrong medications for an extended period of time.”

Treatments for Epilepsy

“At UCLA, our goal is to give personalized care…”

- Can Epilepsy Be Cured? Does Epilepsy Go Away?

Epilepsy is considered a chronic condition that is typically managed rather than cured. The purpose of treatment is to control seizures and improve the individual's quality of life. For Dr. Eliashiv, the end goal of treating epilepsy—whenever possible—is seizure freedom, especially for those patients who have drug-resistant epilepsy.

“Patients are still insufficiently referred to specialized epilepsy centers, where we offer a whole range of treatment options, from electrical devices and surgery to new medications and specialized diets. And it's important to individualize the treatment for each patient based on their unique set of circumstances.”

Common methods of treatment include:

- Epilepsy Medication

Antiepileptic medications (AEDs) are the most common and effective way to manage epilepsy. AEDs can help prevent or reduce the frequency and intensity of seizures. The choice of medication depends on the specific type of epilepsy and the individual's response. In many cases, people with epilepsy can lead normal lives with proper medication management, and the best way to achieve an optimal medication regimen is to seek treatment at a specialized epilepsy center: “We always have new drugs available. There are always new drugs, new clinical trials, especially when you’re getting your treatment from a place like UCLA.”

Clinical Trial: A Study to Test the Efficacy and Safety of Staccato Alprazolam

However, for those patients who develop drug-resistant epilepsy, medications won’t adequately control their seizures and other treatment options should be explored: “Once a patient has failed a few medications, then there's just 4%-5% chance of being seizure free without another type of intervention.”

- Epilepsy Surgery

For some people with focal epilepsy, surgical interventions can remove or disconnect the specific area of the brain where the seizures originate. “Receptive epilepsy surgery is an underutilized tool because it offers 85% seizure freedom in select cases,” argues Dr. Eliashiv. “But there’s a lot of resistance and fear so it requires patient education and risk benefit assessment.” However, this treatment option is only recommended when the patient’s medical team has proven—through an exhaustive battery of tests—that all the seizures are coming from the same specific part of the brain and that area is amenable to surgery without affecting other aspects of the patient’s brain function.

- Neurostimulation and Neuromodulation Devices

There are three major devices available: VNS, RNS, and DBS.

- Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) uses a device that sends electrical signals to the vagus nerve in the neck, which can help reduce seizures in some individuals. “It has been available since 1997 and you don't need to know where the seizures are coming from for this device to work.”

- Responsive Neurostimulation (RNS) is a more recent treatment option. Only approved in the US, this device utilizes a small microchip that monitors brain activity and is programmed to deliver responsive electrical stimulation to reduce seizures. “You don't see the results right away. It takes a few years,” warns Dr. Eliashiv. “But eventually this treatment provides approximately a 75% reduction in seizure frequency and about 15% patients may become seizure free.”

- Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) requires implanting electrodes in the nuclei of the thalamus and generally provides a 75% reduction in seizure frequency. “The DBS devices require less localizing information,” explains Dr. Eliashiv. “That’s helpful because sometimes—despite all our best efforts—we can't pinpoint exactly where the seizures are coming from or the seizures come from multiple places or the network is simply more diffuse… and UCLA is the leading site for this particular treatment.”

Clinical Trial: Medtronic Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) Therapy for Epilepsy

- Diet

In some cases, a ketogenic diet, which is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet, may be recommended, particularly for individuals with drug-resistant epilepsy. “Epilepsy caused by glucose transporter type 1 deficiency syndrome (Glut1DS)—a genetic condition—responds especially well to this kind of treatment.”

Can Epilepsy Kill You?

While epilepsy itself is not typically a life-threatening condition, seizures can sometimes have serious consequences, and in rare cases, they can lead to death.

Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP) is a rare but serious complication of epilepsy where a person with epilepsy dies suddenly and unexpectedly, with no other cause of death identified. While the exact cause of SUDEP is not well understood, it is most often associated with generalized tonic-clonic seizures, especially if they occur during sleep “Two of the major risk factors for SUDEP are drug resistant epilepsy and untreated epilepsy. The best way to avoid SUDEP is to ensure good treatment of seizures,” insists Dr. Eliashiv.

Read More: Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP)—What You Need to Know

However, SUDEP is not the only concern, since accidents and injuries caused by seizures can also result in death: “For instance, drowning is a risk. Driving is a risk. That's why seizure precautions are also important.”

Can Epilepsy Cause Brain Damage?

Most seizures do not cause brain damage, especially if they are brief and well-managed. However, prolonged or uncontrolled seizures—particularly status epilepticus—can potentially result in brain damage. “These patients may need to be admitted to the intensive care unit and be put on certain sedative medications like midazolam or propofol or barbiturates.”

The risk of brain damage is greater when the brain is deprived of oxygen for an extended period during a seizure. This is one reason why it's crucial to seek prompt medical attention for seizures that last longer than a few minutes. And it’s especially important for younger patients: “In the developing brain, time is very important. For infantile spasms, if we don't stop the seizures, then the patients may not reach their milestones.”

It's important to emphasize that the vast majority of people with epilepsy do not experience SUDEP or significant brain damage from seizures. With appropriate medical care and seizure management, the risk of these complications can be minimized. Or as Dr. Eliashiv puts it: “Somebody who has a seizure that lasts 30 seconds once a month? It’s unlikely they're going have brain damage.”

Epilepsy Awareness Month

Epilepsy Awareness Month is an annual observance dedicated to raising awareness about epilepsy. Every November, the month-long campaign aims to educate the public, reduce stigma associated with epilepsy, and promote understanding and support for individuals living with the condition.

In honor of Epilepsy Awareness Month, Dr. Eliashiv described some of the most common misconceptions about epilepsy as well as some key things she wants people to understand about this condition.

Common Misconceptions About Epilepsy

#1 - Genetics are the sole cause of epilepsy. False, says Dr. Eliashiv! “Anybody who has had a traumatic brain injury is susceptible to having a seizure. Anybody who has had intracranial hemorrhage is susceptible to having a seizure.” Genetics may play a role in some cases but there are many causes of epilepsy.

#2 - Women with epilepsy cannot have children. “That’s not necessarily true,” argues Dr. Eliashiv. “Yes, it would be high risk pregnancy. And you need the right medication to avoid fetal abnormalities.” But many female patients with epilepsy can and do give birth to perfectly healthy babies.

#3 - People with epilepsy deserve to be stigmatized. “Don't let epilepsy define you,” insists Dr. Eliashiv. “Patients come to me and say, ‘Oh, I'm an epileptic.’ And I say, ‘No, you're a person with epilepsy. Who you are is a lot more than that and there are a lot of things that you can do. You can still go to medical school. You can still be a lawyer.’ I always tell my patients that they should still follow their dreams and make their lives as meaningful as possible.”

#4 - That seizure freedom is an unrealistic goal. “Never give up on seizure freedom or at least treating your epilepsy with the best possible treatments,” advises Dr. Eliashiv. “Sadly it’s not going to be possible in every situation. But epilepsy patients are often unaware of the full range of treatments that the field of medicine has to offer. So instead of pursuing seizure freedom, they simply accept a future of not being seizure-free.”

Read More: UCLA’s Epilepsy Center Offers Hope to People with Drug-Resistant Seizures

In the end, it comes down to never giving up on the best possible outcome. Or as Dr. Eliashiv puts it: “Be an active participant in your own care. And advocate for yourself, too. You’re the patient. It’s your journey.”