What Is Anatomic Pathology?

A UCLA Doctor Explains

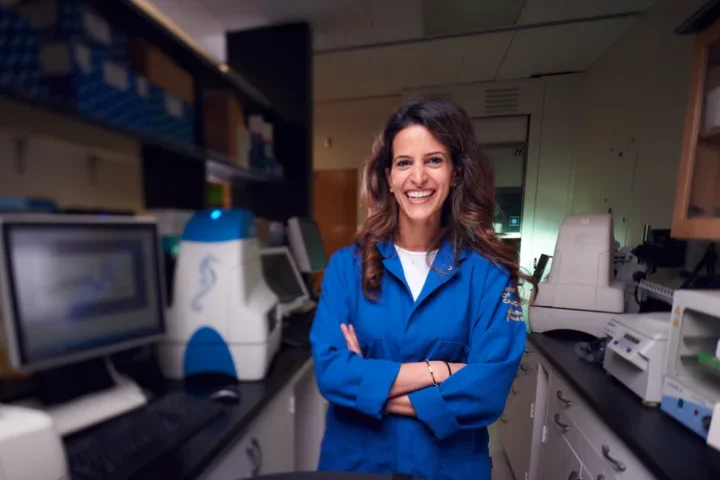

A Day in the Life of Dr. W. Dean Wallace, Chief of Pulmonary Pathology at UCLA

Anatomic pathology is an essential aspect of disease management, particularly as researchers learn more about the genetic targets of today's most common conditions. For this reason, any time is a good time to enter the field.

The Role of an Anatomic Pathologist

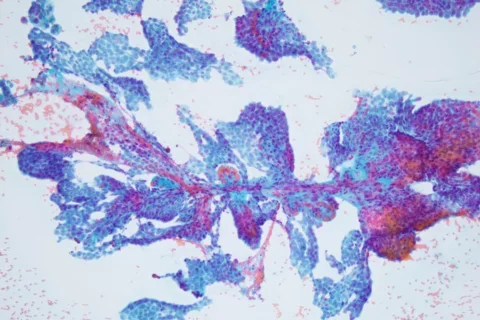

Pathology consists of two branches. Clinical pathology involves the operation of chemistry laboratories or blood banks in hospitals; anatomic pathology analyzes tissue samples both grossly and under the microscope. Pathologists then synthesize elements from the microscope into data from the molecular lab and report back to the physicians who are providing treatment. Even for those in an anatomic environment, there's a lot of clinical and research-oriented interest in the information they develop.

In cancer, especially, individualized, targeted therapy is the future of disease treatment, and anatomic pathologists are central to the diagnostic process.

"There seems to be more interest in pathology now than in the past from graduating medical students, perhaps because of the genetic revolution medicine is undergoing," says W. Dean Wallace, MD, chief of pulmonary pathology at UCLA. "We have so many more tests and testing formats to perform on tissue samples than we did just 10 years ago."

The Day to Day

A pathologist's job can vary by "where" he or she works, both in location and professional focus. Within anatomic pathology, physicians can choose to specialize even further. Dr. Wallace specializes in thoracic pathology, including heart and lung as well as medical renal and autopsy. At UCLA, he's both a researcher and a teacher.

On an average day, Dr. Wallace reviews slides of tissue samples in the morning and makes reports for the clinicians. He may order additional stains or further studies for cases that don't yield a diagnosis on just the initial material. He also will spend time in the gross anatomy room to evaluate surgical samples, such as lung-cancer resections. The afternoon may be spent on research, committee meetings or conferences to review patient cases.

During the entire process, he'll work with pathology residents and participate in resident education.

Because of their importance to the diagnostic process for so many diseases, anatomic pathologists usually have strong connections with providers across multiple specialties in the medical center. To better assess a specimen, for example, a pathologist may need to discuss the clinical picture with the treating physician to find out more about the patient.

"If I have a renal biopsy from a kidney-transplant patient," Dr. Wallace states, "I can usually make a more accurate diagnosis if I know whether or not the person has been taking their anti-rejection medications."

The Appeal of Pathology

Due to these intellectual challenges, pathology offers the chance for an eclectic work experience. "I was attracted to pathology because of the investigative approach," Dr. Wallace says. "You have to accumulate data that may be histological and clinical and put your report together based on your findings."

He also was drawn to the field because, in many pathology practices, it is easier to balance work and home life.

Keep an Open Mind

For anyone interested in pursuing anatomic pathology, Dr. Wallace encourages an open mind throughout medical school.

"Having a narrow focus of interest can limit what you're able to do and where you can work after residency," he says. "Plus, usually the more you learn, the better physician you'll be."

Residents have the option to specialize in anatomic or clinical pathology and shorten their training, but Dr. Wallace cautions against a more compact program for the sake of finishing sooner. "Having the full AP/CP training in pathology may take another year," he says. "But the well-rounded education can open up more possibilities for the future."