Becoming a Doctor: Ky'Tavia Stafford-Carreker

Student Spotlight

How to Get Into UCLA Medical School

Ky'Tavia Stafford-Carreker’s mother kept a scrapbook to document her daughter’s childhood memories and dreams. It captured exactly what a young Stafford-Carreker wanted to be when she grew up: A baby doctor.

She recalls being enthralled by A Baby Story, a documentary series about pregnancy and childbirth.

“It was just so inspiring and powerful to me, even as a kid. The process of creating life was beautiful.”

Early Awareness of Health Disparities

Growing up, Stafford-Carreker’s interest in becoming a doctor made her enjoy going to the doctor. She noticed her family felt differently.

“I started to realize that everybody wasn’t as comfortable with health care as I was.”

She soon learned her family avoided medical care because they’d experienced discrimination from physicians in the past. They were reluctant to put themselves in situations where they knew they might not be respected or treated well.

To make matters worse, they lived in an area where they felt lucky to see physicians at all, let alone physicians who looked like them.

“That made me realize I wanted to go into medicine and be a force for change. It made me push myself.”

Stafford-Carreker’s family, while uncomfortable visiting doctors, didn’t hesitate to encourage their daughter to become one.

Choosing a Medical Specialty

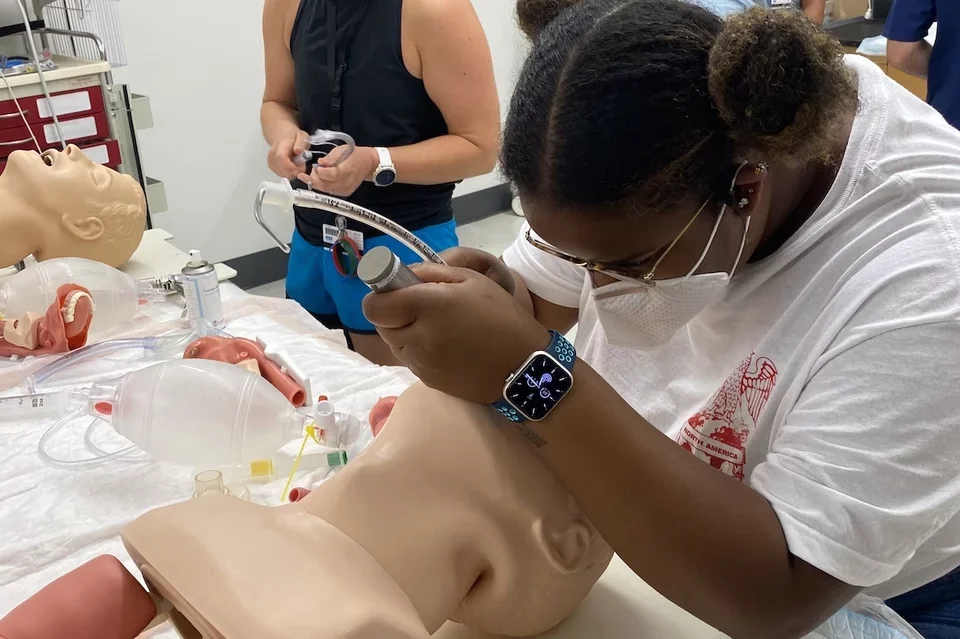

Stafford-Carreker, now part of the PRIME program at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science/David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA (DGSOM), still wants to be a baby doctor (obstetrician).

She’s also not ruling out other specialties.

“I’m just excited and open to anything, honestly,” she says. “I still have the baby doctor preference, but I’m also being exposed to so many different things I never knew about.”

She plans to shadow a variety of physicians to make an informed decision about her specialty.

She’s more sure about what she doesn’t want to do.

“I know I cannot look at tissues all day,” she says with a laugh.

(Surviving) Life as a Med Student

Stafford-Carreker knew people compared being in medical school to drinking water from a fire hose. She now understands the analogy better than ever.

“It's super hard,” she says. “But I think things that bring good can sometimes be difficult. You’re changing in every way, from your social life to how you study. It's kind of a metamorphosis.”

Each day, Stafford-Carreker finds evidence of how much she’s learning. Her interactions with patients demonstrate that every single fact she absorbs actually matters.

For example, when a patient complained about shoulder and hip pain, Stafford-Carreker accurately identified the cause. She remembers speaking with the patient, thinking, Wow, I just asked my professors about this.

She finds these and similar experiences validating.

“I really do understand enough to be able to talk things through with physicians at the top of their craft.”

Unraveling Health Disparities

Stafford-Carreker’s long-term goals encompass joint passions: caring for patients and unraveling health disparities. She plans to incorporate her knowledge of history and social sciences into her medical career.

“I came to this field to help, to have a positive impact.”

She studied history and African-American studies during undergrad at UCLA. Her education, combined with her personal and familial history, gives her a comprehensive understanding of the causes and consequences of health disparities.

“I want to make sure people know that the disparities and issues we have today are continuities and not just random anomalies.”

When people understand historical context, she says, the underlying causes of present issues make more sense.

While she was completing her honors thesis in reproductive racism, she learned how high maternal mortality rates among Black women have roots in the early days of obstetrics and gynecology. Practitioners conducted experiments on slave women, but the benefits were translated to White women.

“The project helped me better understand the current state of health disparities and how they came to be and also connect them with experiences in my family,” she says. “So for me, it makes perfect sense to see the continuity of why Black and Brown women are treated so horribly.”

Stafford-Carreker wants to ensure this makes sense to everyone—to open new conversations and expose the often hidden truths of the past in order to build a better future.

She’s already started working toward this end by serving as co-president of her Charles R. Drew University class, joining the board for the Minority Health Conference, and mentoring aspiring medical students from her hometown.

Breaking Down Barriers to Health Care

Stafford-Carreker also has a passion for expanding language access in medicine. She recalls shadowing a provider who, despite not being from a Hispanic background, completed an entire visit in Spanish. Stafford-Carreker aspires to perfect her Spanish enough to do the same thing.

“A lot of people don't have access to care, let alone a language that fits them,” says Stafford-Carreker, who grew up in an area where multiple languages were spoken.

She hopes to mediate barriers for her Spanish-speaking patients and then move on to learning as many other languages as possible.

“Just being able to communicate with folks, even when I'm not able to speak their language, is important to me,” she says. “As a physician, I'm not only a physician for people who look like me or who speak the same language as me.”

Quick Tips for Future Med Students

Follow your heart when choosing a medical school.

Stafford-Carreker chose DGSOM, despite a location far from home and family.

“There was just something about the feeling I had when I came to Second Look. The people and the support here made me feel comfortable enough to leave my family again.”

Trust yourself, especially during exams.

Stafford-Carreker suspects second-guessing herself during exams is hurting, not helping, her performance.

Practice self-care.

Stafford-Carreker knows medical school and her future career will only get harder. She wants to create a strong foundation of self-care and self-love to help her get through it.

“So overall, I just want to be kinder to myself, as kind as I am to the future patients I want to take care of.”

FAQ for Future Med Students

What Is a First-Generation College Student?

A first-generation college student is the first in their family to attend college. Read more about first-generation medical students at the DGSOM.

According to the most recent report available from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC):

- The average cost of attending one year of private medical school in the United States is $39,905.

- The average cost of attending one year of public medical school in the United States is $62,570.

See the costs associated with attending medical school at the DGSOM.

How Long Is Medical School?

Many medical schools offer a four-year medical education curriculum. After students complete this core curriculum, they spend several (3-7) more years in residency training for their chosen specialty.

How Hard Is Medical School?

Medical school is hard because being an outstanding physician or physician scientist is hard. Most medical schools design rigorous curriculums that prepare medical students for the range of challenges they’ll encounter every day as practicing physicians.