Becoming a Doctor Underscores the Importance of Being Human

Student Spotlight

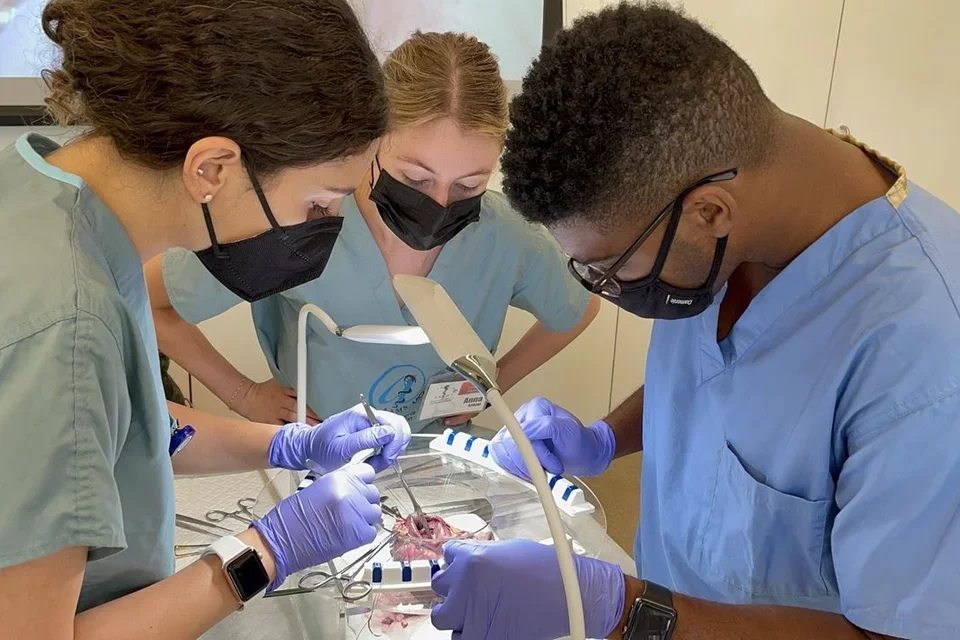

Meet Myles Anderson

Medical student Myles Anderson grew up in a small town outside Houston, Texas. Unlike many of his peers, Myles can’t recall the exact moment he realized he wanted to become a doctor. He’s had this goal as far back as he can remember.

Myles was just 11 months old when his father passed away from complications related to pulmonary hypertension. He unfortunately never got to know his father, but he found inspiration and motivation in his memory. He wanted to grow up and help heal people—to protect them from the pain he, his father, and his family faced.

As Myles got older, he learned more details about his father’s case.

“Throughout the years, he got diagnosed with things like asthma and emphysema; nobody could figure it out,” Myles says. “By the time they diagnosed him with pulmonary hypertension, it was already too late.”

The doctors said Myles’s 35-year-old father had the heart of a 75-year-old man. His premature death was tragic, but unfortunately, not an anomaly. Myles learned that countless others like his father experience more negative outcomes than people from other groups with the same health conditions.

“African Americans have an increased risk of mortality not only when it comes to pulmonary hypertension but also when it comes to many other medical conditions as well,” Myles explains.

His motivations became more specific as his understanding of systemic health inequities became more clear. He envisioned himself as a physician and advocate who shows up for under-resourced and vulnerable populations.

Fun fact: Myles sang in school and church choirs throughout his childhood. While he no longer belongs to any organized vocal groups, he remains passionate about music and often uses it as a tool to de-stress

Connecting with an Unexpected Passion

Today, Myles is pursuing his goal to alleviate health inequities as a student in the dual-degree medical education program offered jointly by the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA (DGSOM) and the Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science (CDU). In addition to completing DGSOM's HEALS medical school curriculum, Myles also does coursework focused on health disparities, social justice leadership, and caring for diverse and disadvantaged populations.

Myles had fallen in love with UCLA while attending DGSOM’s Summer Health Professions Education Program (SHPEP) as an undergraduate student. Returning to attend medical school felt like a dream come true.

He loves Southern California’s sunshine, beaches, and mountains but ranks his supportive, diverse community above all the other benefits that come with attending med school at UCLA.

He has supportive classmates and mentors from myriad different backgrounds. He has opportunities to treat patients from all walks of life at hospitals and training sites throughout Los Angeles. He can seek mentorship, consulting, and advice from experts in any medical specialty.

“You can literally learn anything you want here at UCLA.”

You can also learn things you never knew you wanted to.

Drawn to the medical profession by his father’s experience with pulmonary hypertension, Myles had always assumed he’d specialize in cardiology. He discovered a passion for anesthesiology, a specialty he’d never given much thought, while shadowing some of his mentors, Jason S. Lee, MD and Cecilia Canales, MD, MPH.

The epiphany came as Myles observed residents talking to patients prior to surgery. They listened to concerns, fears, and offered much needed comfort. Seeing this deep human connection and compassion drew Myles to anesthesiology.

“You get to be there for the patient in what’s probably the scariest time of their life, and that really resonates with me,” Myles says. “I want to be with people of color who may be scared of anesthesia and surgery.”

The core value of being present and human also keeps Myles grounded during challenging times in his training, such as second-year clerkships.

Clerkships provide medical students with supervised clinical practice. Transitioning from the classroom to the clinic—and handling the pressures and unpredictability of patient interactions—can be stressful for many students.

Myles found that remembering to be human can alleviate some of the stress that comes with learning to be a doctor.

“A lot of times, patients will come to the physician’s office or the emergency room alone,” he says. “You may be the only person they’re talking to. You’re their only point of connection at the moment.”

Finding People to Lean On

Myles has some simple yet powerful advice for anyone applying to medical school or planning to: never give up.

“You’ll have good days. You’ll have bad days,” he says. “No matter how hard it gets, embrace the highs and lows, feel every single emotion, but just keep going, and eventually, you’ll find yourself on the other end.”

Freshman year of college tested Myles’s resolve. Struggling in chemistry and math, he grew frustrated enough to consider turning his back on medicine.

Fortunately, a supportive uncle gave Myles the advice he now holds dear and shares with others.

“Just keep going. Keep pressing through,” his uncle said, reminding Myles that he’d been talking about becoming a doctor his entire life—too long to quit because of a few hard months.

Instead of quitting, Myles committed. He redoubled his studying, and eventually, brought his grades up.

“Find a good support system. You’re going to need people to lean on,” Myles tells future medical students, knowing they’ll have a much better time not giving up if they surround themselves with people who won’t let that happen.

“When things get hectic or you feel like giving up, you’ll need people to pull you out of that dark place.”

Myles built strong support systems at school by joining organizations that align with his values, such as Student National Medical Association (SNMA), which focuses on the needs of medical students of color and Black Men in White Coats, which works to increase the number of Black male physicians practicing medicine, and ultimately, to alleviate health disparities.

The Pursuit of Kindness

During his time so far at DGSOM, Myles has earned a reputation for being exceptionally nice. Classmates can always count on him to offer a smile, a warm hug, and a sympathetic ear when they need to talk.

“Having someone to talk to can really brighten someone’s day, and let them know they’re not alone, even when they feel like it,” Myles says.

Myles intentionally pursues kindness every day—something he learned from and shares with his family.

“We have a family culture of being very giving to people,” he says. “We like to show love. We’re very big on our faith as well. We like to share the love and share whatever we can with people, whether they need anything or not. We just love to give.”

The pursuit of kindness relates to another key lesson Myles has learned.

“The most important thing I’ve learned in medical school doesn’t involve medicine,” he says. “Relationships are everything.”

Beneath all the learning, training, and experience, he sees relationships as the true measure of success, both as the human being he is and the compassionate physician he’ll soon become.